Hoang Dang Khoa

Translator, Artist Trinh Lu

|

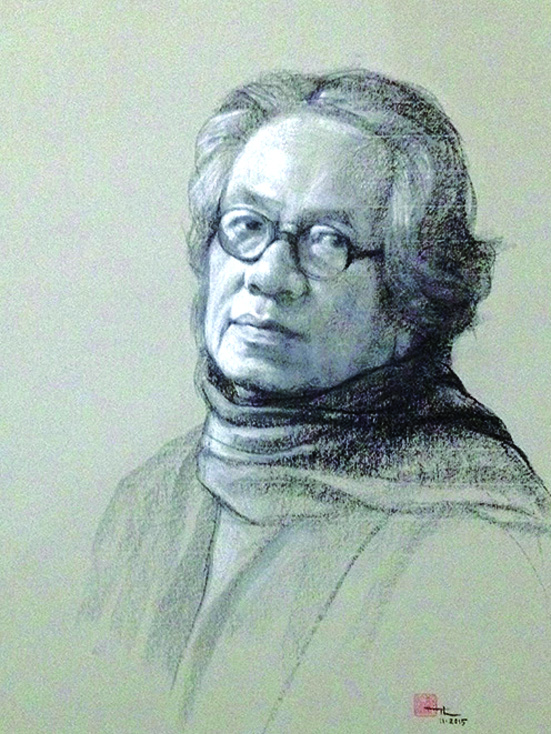

| Trinh Lu (self portrait) |

He travels, gets involved and active in various fields, spends much of his time overseas, but seems to remain an introvert taking refuge in nature to fathom his own psyche – an emotional and aesthetic man, unchangeably. His paintings, translations and writings, and his life itself, are richly imbued with poetry, music and a melancholy beauty. The idiosyncratic story of his life and career which he shares with our Army Magazine of Art & Literature (AMAL) would consolidate the silent belief in each of us about the seductive mystery of human destiny and art. - Born into a family of many painters, you also graduated from Hanoi University of Mining and Geology, then got your Master of Science in Communications in America, how come you break off from such a formative conditioning and become a translator?

+ Well, that’s simply forced by circumstances. I just did what I have to do. I should say jobs choose me. I can only choose my own dreams.

- May we hear more about how the jobs choose you?

+ Nothing extraordinary about that. I think that happens to everyone.

My parents were painters, nurturing us by their profession, so we grew up with a love of art, and naturally learned how to draw and paint. My father (painter Trinh Huu Ngoc – AMAL) used to say “Fisherman’s children know how to swim, naturally”. So that’s a simple story.

But my study in the Mining and Geology College was quite unexpected. In 1965, high school students were selected into colleges and universities not through standard entry-exams of their scholastic capabilities. We were allowed to submit our aspirations, and a Selection Committee would decide who should study what and where, based on the national education plans, our family background and high school scorecards. My first aspiration was the School of Industrial Arts, where my father was being dean of Interior Decoration Faculty; and Architecture was the second one. But I was screened out of high education, down to a local makeshift one-year primary-school-teacher-training program called “Ten Plus One” (ten years of general education plus one year of vocational training – AMAL). Never aspire to that kind of job, I refused it. By the time a friend of my father moved to clear my family background, making me eligible for university, only the Mining and Geology Department of the Polytechnics was still accepting new students to its Mining Construction Faculty. (In 1967, this Department was separated from the Polytechnics to become the Mining and Geology College – AMAL). That’s why I studied mining construction, comforting myself that it’s still having some architectural elements, and my luck was still not as bad as that of many young talents who were denied higher education due to their family background.

-Back then, family background must be a very serious issue?

+ Oh yes, my family’s social class was “artistic petit-bourgeois” – therefore being doubly suspicious (laughs). Petit-bourgeois was an anti-revolutionary class; and artists were the most individualistic and unreliable elements in society – according to social classification at that time.

- But in the end, mining construction profession also did not select you. Now, how did the radio career choose you?

+ So you know it. I have 16 years working as a radio announcer and program producer in the Voice of Vietnam, a rather long time, and completely unplanned.

In 1970, I completed my undergraduate program at the University of Mining and Geology, but being not a member of the Youth Union, I was denied my diploma. Because of that, I refused the job at Cam Pha coal mine assigned to me by the then Ministry of Education, and got disciplined. During my student years, I had some technical innovations that improved productivity of tunnel mining, and translated technical documentation for the Technical Department of the Ministry of Electricity and Coal (now the Ministry of Industry and Trade - AMAL). The head of that Department, Mr. Tran Anh Vinh, offered me a communication position tasked with designing and publishing a technical journal. While official recruitment decision was still pending, Mr. Vinh already took me along as his assistant in his field trips, and I also submitted a master plan for his dream journal. Then, he was sent on a mission to the Soviet Union, and sacked upon his return, supposedly because of his “revisionism”, and so was my chance to work with him.

Unemployed at home, I heard that Radio the Voice of Vietnam was recruiting announcers for the English broadcasts calling American GI’s in Viet Nam. I passed the audition – some written translations and recorded readings in the studio – was recruited, but as a “contributor” only, with a monthly fee of VND 30, not a salaried staff. It was in 1972.

- How and when did you learn English so that you could pass such an audition so easily?

+ I had my first lessons in my childhood, but started learning English seriously in my student years, just by myself, with two dictionaries – English-Russian and Russian-Vietnamese; and was criticized as “sneakily learning the language of the enemy.” 1971 was a good English-learning year. Still jobless, I spent only couple of days a week painting paid propaganda posters for food, then devote my time to learn in the National Library, using the library card of a teacher-friend and timid smiles for the lady librarian to get the books and dictionaries I wanted. Fortunately, a close welder-friend of mine - very handy in electronics – successfully resurrected a bomb-damaged old radio receiver that brought the BBC English by Radio and Voice of America’s Standard English programs to teach me pronunciation and intonation. Falling in love with the deeply sonorous voice of Willis Conover in his Voice of America’s Jazz Hour, I got tamed with that kind of American accent, which made me much wanted for the Calling GIs programs of the Voice of Viet Nam.

- After 16 years working in the Voice of Viet Nam, what made you leave a job you were so good at and became a student of communications in so far away as the U.S.A.?

+ Well, if you cannot pursue your dream in life, and your own true nature is the only choice, you would have to navigate through unexpected turning points. I did love my radio work, became a government employee after a few years, was lowest in announcer’s payroll because I don’t have university diploma in English. Some features I produced during the war years are still alive now, like the Music Box and the Sunday Show. Beside program producing and announcing, I also designed international communication devices for Voice of Viet Nam – brochures, program leaflets, greeting cards; translated and wrote training materials for radio journalists, and served as National Coordinator of the Asia-Pacific Institute for Broadcasting Development in Viet Nam. I was also moonlighting as a freelance translator and voice talent for television and films.

In 1984, my salary at the radio got a double rise following the success of my translating and voice-dubbing for the PBS epic series “Viet Nam-A Television History”, which was premiered in Viet Nam national television for 13 consecutive days. Two years later, frustrated with the post-war changes in both personnel and professional culture at Voice of Viet Nam, I left the radio, starting my new job as a National Programme Officer at the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), managing the Information, Education and Communication projects funded by this fund in our country.

|

| US Ambassador Ted Osius congratulating Trinh Lu after delivering the opening remarks for the exhibition Plein Air Painting in America in Ha Noi (March 2015). Photograph provided by Trinh Lu. |

- So you chose that job? And you went to America to study communications as a UN fellow?

+ About the UN job, yes, that’s a choice I made by survival instinct. But my scholarship was provided by the Cornell University, not the United Nations. Halfway in my graduate programme there, Mr. Van Arandon – a Deputy Executive Director of UNFPA – offered me his personal secretary post in New York City, but I avoided that over a lunch with him, presented him with one of my landscape paintings in oil as my sincere thanks for his goodwill. I could never be a good secretary. And I was being in love with the beautiful landscape of Ithaca, as well as my study, which was even leading me to a Ph.D. program in the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

- But you did not take that chance for a academic carrier?

+ No, I did not. After two years in Cornell Graduate School, I got a feeling that I am not a born academic; and I was in pressing need for some income to keep my family afloat. I took my wife and two children with me to Cornell, you know. So, after graduation, I went to New York City, because UNFPA HQs had contracted me to design a multi-media social marketing package to support its global fund raising activities. That’s how we started living in New York City. After that contract, I did many different things for my family to stay on there, for my kids to make the best of the available educational opportunities.

- Would you tell us about some of those different things that you did?

+ Well, I only did what I can do. Here are some examples: freelance translator and voice talent for advertising agencies with clients that serve the Vietnamese communities in North America; partnership with the Viet Nam Courier from Ha Noi to publish Viet Nam Opportunitie, a bi-monthly, 16-pages newsletter informing US businesses about Viet Nam as an opening market. By the way, I think the New York-Ha Noi computer-modem connection I rigged up with the Courier might be the first between the two countries. For more than a year, I joined a group of Vietnamese-American journalists to produce Vietnamese-language television programs for the Direct TV network. And for almost 3 years, I worked as Communication Designer for the Citigroup Private Bank’s Marketing Department. After the 9/11 terrorist attack at the Twin Towers, and when our two children were already in college, my wife and I returned home to Hanoi. That was in 2002.

- I remember your Vietnamese translation of the novel Life of Pi won the 2004 Translation Award of the Hanoi Writers Association, and the same award the following year by the Vietnam Writers Association. Ever since, you have become a well-known translator with dozens other very famous titles. I see you became a translator when being back home. What steered you onto this very hard but attractive carrier of literary translation?

+ Just by chance, I should say. Back home, when I still didn’t know how to make a living, some young fellas came asking if I could translate that book. I say yes after one night browsing through it. But perhaps that’s not quite by chance. I used to learn English by translating the texts I love. In the radio years, my translations of some foreign short stories were published by the Art & Literature Magazine; and my translation of Frank Hardy’s The Yarns of Billy Borker was published in book form by the then New Works Publishing House. However, it’s true that the unexpected success of my translation of Life of Pi did encourage me to devote more time to literary translation, and became a translator as being called. - So, you found the answer to your question of how to make a living in Viet Nam?

+ Well, not exactly. I lived mostly by the income from my contracted works as a strategic and development communications specialist.

- Strategic and development communications – What do you do specifically?

+ Bear with me, here are some specific works to answer your question: I helped the UNFPA Field Office in Ha Noi to find out why the size of the program in Vietnam is much smaller than before, but the office staff has increased several times; then proposed a more appropriate workflow and staffing pattern, plus a set of quality control procedure. I assisted the Ho Chi Minh National Political Academy to integrate population and development contents with its curricula of sociology. With the General Statistics Office, I help the writing and designing communication materials to support the operations of the general census. With the Ha Noi School of Public Health, I helped them design long and short term development strategies, complete with accompanied communication strategies. With the Atlantic Philanthropies – which invested USD380 million in health care and high education in Viet Nam - I helped them review and share their Viet Nam experiences with the world of potential philanthropists, as well as with the Vietnamese government, by writing a series of three booklets about their works and lessons learned from their operations in Viet Nam. I should stop my listing here. Your readers must be bored now.

- (laugh) Well, now I know you are also a professional communications expert. We should have a chance to talk more about this. Allow me to go back to your translation work. Translator Dao Tuan Anh has said that a translator whose target language is Vietnamese should necessarily be well versed in the source language, culture and the meaning of the original texts, and should sufficiently be highly literary in the Vietnamese language. Would you like to add anything else?

+ I guess that’s quite enough, as language itself reflects all other aspects of the intellect. But if need be, perhaps we might add sincerity by nature, rich life experience, and some doses of perfectionist at work, I think.

- Yes, I guess you’re right. Now let’s talk about your translation of Norwegian Wood. Reading it the first time, I was so impressed and obsessed that I did not want to read it again, being fearful that my first impression and obsession might be diminished. Then, I took turn to read every Vietnamese translation of Murakami’s works, with much less impressions, though I still like them. Lately I have come across more and more unfavourable critics of Murakami’s later works. Many international seminars have discussed about how and why readers are so conflicting in their reception and appreciation of his works. What would you say of this author, whose Norwegian Wood has made you such a famous translator in Viet Nam?

+ For me, Norwegian Wood is the author’s simple and sincere narrative, thus conquers quite a universal readership. Later on, Murakami seems interested more in “innovating” the how of writing. These works are in league with the mainstream belief that contemporary literature must be hard to understand, things should be fragmented, confused, impersonal, weird... Murakami’s literary world became more and more magical, dreamlike, woven by real and surreal strands, and always with his own cynical smile hovering above. Perhaps that’s why his readers are being divided, segregated. I think this is also a remarkable success of Murakami.

- That’s probably true (laughs). Let’s put aside literature for a while. Now I want to know, for you, in addition to your gains in the English language, what would be the “surplus value” of your long years living, working, studying in America?

+ Well, I would say it’s a simple revelation, that we humans are the same everywhere, not different in our elemental greed, anger and desire; and everyone wants to belong to a place called home.

- As simple as that?

+ Yes, as simple as that.

- You have travelled a lot, got involved and active in various fields and been overseas for a long time but it seems you are still an introvert, taking refuge in nature to fathom your own psyche. The books you chose to translate, your writings and paintings give me such feelings about you ...

+ Is that so? People who know me only from my words and paintings are all very much like you – feeling about me like that. But those who know me well in person would speak about me quite differently (laughs).

- You know what, for me, your paintings, your translations and writings, and your life itself, are all richly imbued with poetry, music and a melancholy beauty. It seems you remain an emotional and aesthetical man, unchangeably. Speaking of you paintings, I’ve learned that your exhibition Plein Air Painting in America, with your book of the same title in early 2015 was unprecedented in our country, a significant artistic event in the history of Vietnam-USA relationship, opened in Ha Noi by the then US Ambassador Ted Osius. In a life course like yours, with so many changes and occupations, how has the painter in you survived and now recognized?

+ My father used to say, as I already quoted, “Fishermen’s children know how to swim, naturally”. We the children grew up in our parents’ painting studio, learning the craft along with their students. With maturity, I have realized that our spiritual heritance from such a family life is a natural behaviour pattern that takes painting, music and creative labours in general as a way of life, not just a profession or a carrier.

I remember I love drawing when still don’t know how to hold a pencil. Luckily, I was allowed to accompany many of my parents’ plein-air painting trips, and learned the basics in a natural way at home. In the 4th and 5th grades, I won some awards of the annual international children’s painting competition sponsored by an Indian art magazine. In my student years during the war, evacuated to a mountain campus by the Ki Cung river, I spent most of my idle time drawing and painting in the jungle. In the late 1970s, I participated in exhibitions of Hanoi’s young artists, and a collector from Sweden started buying my paintings, mostly abstract ones. While in the Voice of Vietnam, being in Pnom Penh as a specialist to train the Cambodian radio announcers for their English programmes, I produced a series of portraits in pastel and became their special friend. During two years at Cornell University, I joined a local group of artists, had two solo exhibitions of Ithaca’s landscapes, even selected by the Ithaca Journal as Artist of the Year 1993. My paintings are still hanging in the conference room of Cornell’s Communications Department, in the lobby of the Ithaca Talent Education School, and the living rooms of many local families. In New York City, toiling to survive, I still managed to paint, even earned some income from portraiture. Painting helps me to be calm and balanced, so I keep on with it wherever I am, along with whatever I have to do to survive. Perhaps I love plein air painting best. I love to be outdoor in nature, feeling I am part of the harmony so alive around me. It’s true that I never wonder if I am a painter or not. The first time I was called a painter is by some articles on the Ithaca Journal and the Cornell Sun, written about my exhibitions there. It was 1992-1993, the Cold War still lingered, such an appreciation of the paintings by a Vietnamese scholarship student in America was really something. At home, I think I got popularly known as a painter only after my Plein Air Painting in America exhibition.

I think if you are born in love with something, you always find a way to be with it, come what may.

- Thank your for sharing with us such a private story. Please allow me to ask you another private question: Born and grew up, as poet Duong Tuong has very well said, “in a Hanoi family of intellectuals and artists with many talented members”, have you ever been pressured by the fame of your own family

+ You mean the pressure that I have to live and become an artist in someway to be worthy of my family?

- Yes, that’s what I mean.

+ If so, my answer is Never. My decisions in life and work have all been made by survival instinct and natural preferences, never by a forced effort to be as good as anyone else. My obsession is living, not trying to be worthy of anybody or anything. For me, as I said, making art is a way of life, not just painting canvases, chiselling sculptures, playing music or writing stories and poems.

- Thank you so much for sharing the story of your life with our readers of Army Magazine of Arts and Literature.

Translated by HIEN NGOC